In a previous post, I showed you the Green Man Inn as it was. It’s still there, not quite the same, but easy to recognize.

Litchfield House aka deGriffith House, is the building on the left with the trees on the balcony.

Also still in existence is the house I turned into deGriffith House. Currently known as Litchfield House, No. 15 St. James’s Square, it stands in a corner of the square next to the London Library. You can see some interiors here.

You can read more about the house here at Patrick Baty’s blog.

St. James’s Square in 1812, image from Ackermann’s Repository.

St. James’s Square looked very different in the time of my story.

“In the centre is a large circular sheet of water, six or seven feet deep, from the middle of which rises a fine equestrian statue of William III. Erected here within these few years.” Thomas Allen, History & Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark ... Vol 4 (1829).

Apparently, the pool was still there in the 1839 edition.

Another, much later writer has this to say about the pool: “The basin of water was not even then removed, and is still remembered by many persons now living, the stagnant slimy pool having only been finally drained within the last fifty years, after one of our periodical panics of cholera, when the existing garden was laid out and planted with trees.” Arthur Irwin Dasent, The History of St. James's Square and the Foundation of the West End of London: With a Glimpse of Whitehall in the Reign of Charles the Second. (1895)

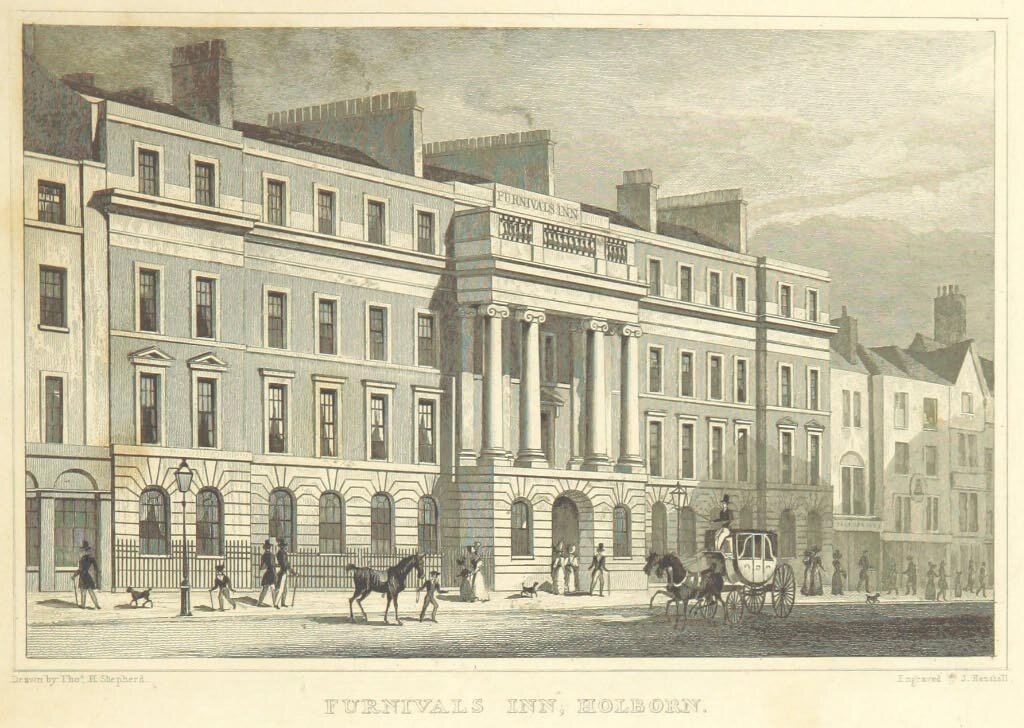

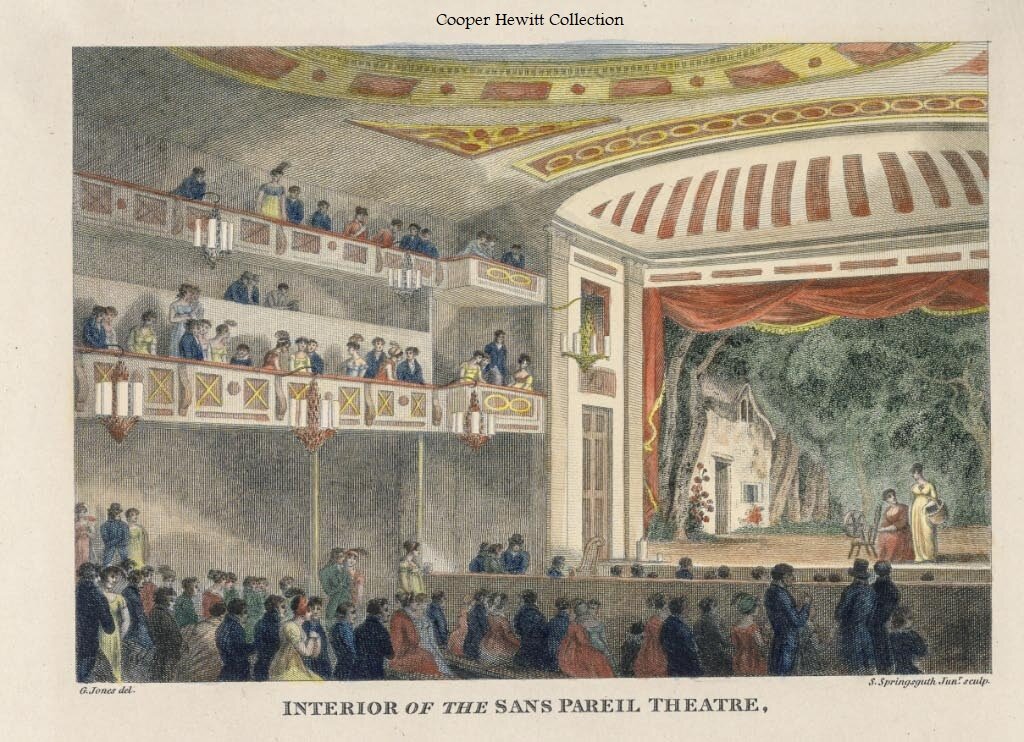

Images L-R:

Furnival's Inn, Holborn was demolished in the 1890s.

Lord Grosvenor's Gallery, Park Lane - Shepherd, Metropolitan Improvements (1828)—Grosvenor House was my model for Ashmont House. It was demolished sometime about 1926-27. A hotel now stands on the spot.

The Hanover Square Rooms, where the fancy fair takes place in my story, was demolished in 1900.

The Adelphi (the image dates to when it was the Sans Pareil) theater, which has been renovated and rebuilt and enlarged over the years, remains in active use.

Charles Cotton’s Fishing House, photo by Neil Gibbs 2 August 2006. Attribution Neil Gibbs

And this is the Fishing House, which I moved from Derbyshire to Surrey for story purposes. You can see other images here at Derbyshire Life.